- Monday, 16 February 2026

- Have a HOT TIP? Call 704-276-6587 or E-mail us At LH@LincolnHerald.com

Cherokee Expedition

The Cherokee Expedition of 1776 blazed a path of destruction

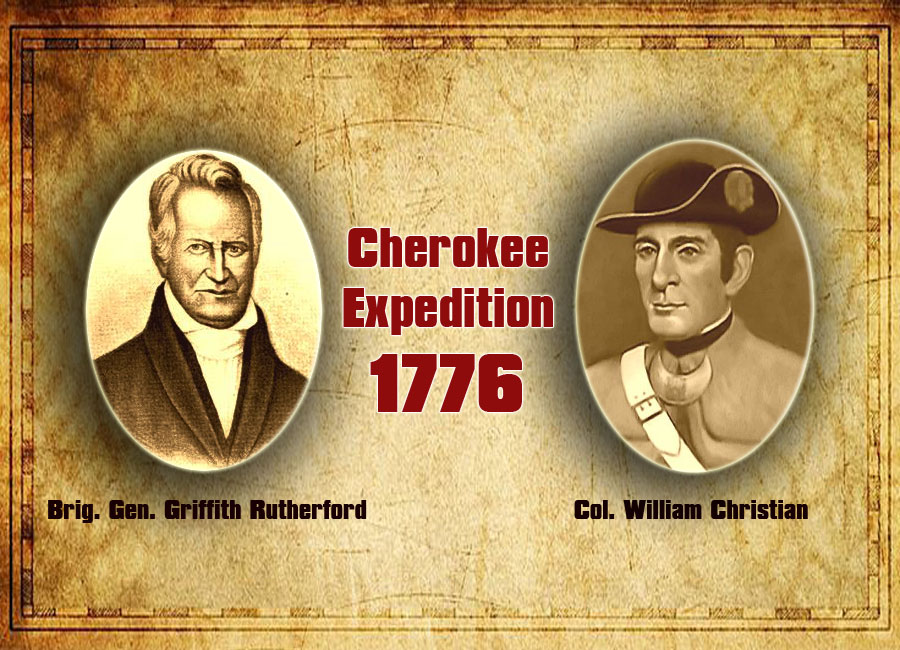

Between August and September 1776, thousands of Continental soldiers and militia from Virginia, Georgia and both North and South Carolina descended upon the Lower and Valley towns of the Cherokee Indians. Led by military officers Griffith Rutherford (North Carolina), William Christian (Virginia), and Andrew Williamson (South Carolina), the Cherokee Expedition of 1776 blazed a path of destruction through Cherokee Country by wiping out entire communities while displacing thousands of people. As the revolutionary leadership justified its course of action: the “attempts by John Stuart [British superintendent for Indian affairs in the South] …to stir up the Savage Indians to attack our Western frontier…particularly the Cherokees” and the resulting attacks “upon our settlements, [who] burned several Houses and Murdered about sixty Persons” necessitated such a response. It should be noted, though, that the attacks were not made explicitly at Stuart’s instigation and were only carried out by Cherokee dissidents known as “Chickamauga”— led by Dragging Canoe—who had grown frustrated with settlers’ incessant encroachments upon Cherokee lands. In the minds of the Chickamauga, violence was the only option left after centuries of diplomacy and trade that resulted in treaties of dispossession. Therefore, in August and September 1776, the revolutionaries responded to the Chickamauga’s’ initial attacks with even more destructive violence of their own. Fortunately for historians, the Filson Historical Society possesses the journal of William Dells, a Cherokee Expedition soldier who tracked and detailed the entire foray into Cherokee Country.

One of the first important details that we get from William Dells’s “A Journall of the Motions of the Continentall Armey…against the Cherokee Indians” is how much Native Americans were on the minds of the revolutionaries throughout the war, their anxieties about the loyalties of those various Indigenous groups, and the important roles Native peoples played in that conflict, as either allies or foes. While the Cherokees were, as Dells put it, “Suspect to be a Grand Enemey to the Americans Liberty,” other Indigenous groups, like the Catawba, allied themselves with the revolutionaries, which explains why “33 Catawba Indians” accompanied the expedition and guided American forces into the valley towns. In contrast to the popular histories about the American Revolution that depict that struggle as a civil war and a war of revolution, the actual conflict was also one that involved Native Americans, as evidenced by primary sources like Dells’s journal. In other words, the Indigenous peoples of North America were not casual observers or mere sideshows to the larger revolutionary struggle being waged in 1776.

The journal also offers a sprawling panoramic tour of Cherokee Country on the eve of revolution. Dells described Cherokee territories in western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee as a mix of mountains, bogs, valleys, rivers, glades, and a few roads, although he focused especially on the “Impregnable” mountains that he considered among the “Most Delightfull prospect[s] As Ever Your Eyes Beheld.” Travelling along these lands often proved treacherous, as Dells consistently noted the mountainous terrain being “very Steap and Dangerous being… Very Narrow” and the glades exceedingly “boggy” and wet. Dells further demonstrated an intimate knowledge of the land by reliably identifying landmarks such as the Pidgeon River, Hominy Creek, Big and Little Swannanoa Rivers, Rich Land Creek, and French Broad River. More importantly, Dells also captured the intercultural and cosmopolitan dimensions of Cherokee Country. He observed how deerskin traders like “one Scotts” and “one Hicks,” along with other “Wite men,” lived on plantations nearby and in Cherokee towns, with “their [Cherokee wives] and Children.” And he noted that several Cherokee individuals spoke “good English,” a reflection of the intimate interactions between Cherokee and European worlds. He also mentioned the several “Negroes” who lived in Cherokee towns, either as freedmen or runaway slaves. Regarding Cherokee towns, Dells often remarked how Cherokee communities comprised “100 Houses” with hundreds of “Acres of Corn,” horses, cattle, and other livestock, which resembled the colonial towns that Dells and the other soldiers came from.

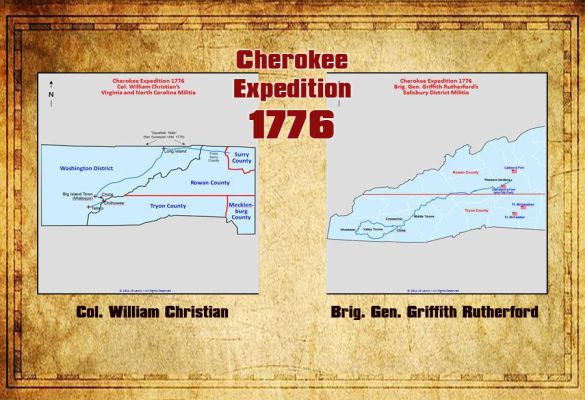

After the British instigated multiple Cherokee raids in July of 1776, the governments of North and South Carolina coordinated an offensive with the governments of Georgia and Virginia. North Carolinians under Brigadier General Griffith Rutherford were to rendezvous with Col. Andrew Williamson's South Carolinians and attack the lower and middle Cherokee settlements. The Virginians under Col. William Christian would march south and west and strike the Overhill Cherokees, while the Georgians would strike north and attack the Indian settlements in northern Georgia and South Carolina.

While the locals were waiting for Col. Christian, the army under Brigadier General Griffith Rutherford assembled at Pleasant Gardens and commenced their westward march in late August or early September toward the Middle Towns in anticipation of linking up with the South Carolinians under Col. Andrew Williamson. Word reached camp of the troubles on the Holston River and Brigadier General Rutherford ordered the Surry County Regiment to divide its men and to send half up to the Hoston settlement. Col. Joseph Williams assembled eleven companies and marched them back to Richmond then on to Holston. Col. Martin Armstrong and his eleven companies from Surry County continued their march with Brigadier General Rutherford and the rest of the Salisbury District Militia.

The army of Col. William Christian was made up of about 1,800 men and marched on October 6, 1776, from the Double Spring camp toward the Indian towns. They went down Lick Creek, in present Greene County to its junction with the Nolichucky River. During the night while the army was camped here, Ellis Hardin, a trader at the Cherokee towns, came into camp with information that the Indians were waiting on the south side of the French Broad River to contest the crossing. From the camp at the mouth of Lick Creek the army marched across the Nolichucky and up Long Creek to its head, then down Dumplin’ Creek to the French Broad River. The army's march was evidently along the Great War Path of the Indians, and the ford across the French Broad was near Buckingham Island.

Before the army reached the ford they were met by Fallin, a trader who had a white flag, but this was disregarded by Col. William Christian. The Cherokee Nation was divided. One faction, led by Chief Dragging Canoe who had been wounded at the battle of Island Flats, wanted to abandon the towns along the Little Tennessee River and withdraw further down the Holston River. The elders and others of the tribe wanted to remain in the beloved towns along the Little Tennessee River. This faction prevailed, and the Cherokees sent Nathaniel Gist to seek peace from Col. Christian. Later, Dragging Canoe, with many young Cherokees and some Creeks, would prevail and make many vicious raids against the settlers from the Chickamauga towns in the vicinity of the present day Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Col. Christian, having been told the Indians were prepared to contest the fording of the French Broad River at Buckingham Island, attempted a ruse. He had his men light a fire and pitch tents for each mess, as if the army meant to remain in camp on the north side of the French Broad River for several days. At 8 pm, he took 1,100 men, marched about four miles below Buckingham Island and crossed the river at the ford discovered there by some scouts from Capt. John Sevier's company. It was the intention of Col. Christian to attack the Indians drawn up to oppose the crossing of the river from behind before sunrise.

To Col. Christian's surprise there was no Indian force there. It is possible the crossing of the French Broad River was made the night of October 15, 1776. Col. Christian had stated in a report from the Double Spring Camp on October 6, 1776, that it was his intention to cross the French Broad River on October 15th. Col. Christian allowed his men to remain in camp that day to dry their equipment and clothes which had gotten wet at the crossing made at the lower ford. While in camp on the south bank of French Broad River, in what is now Sevier County, the scout and traders from the Cherokee towns came in and reported that many of the Indian warriors had taken their families and fled south to the Hiwassee River, in present day McMinn, Meigs, and Bradley Counties.

After spending the following day in camp, the army resumed its march to the towns of the Overhill Cherokees along the Little Tennessee River, probably on October 16th or October 17th. From the fording of the French Broad River to Toqua Ford on the Little Tennessee River, the march led the army up the valley of Boyd's Creek, in present day Sevier County, and down Ellejoy Creek from its source in Sevier County to where it runs into Little River in present-day Blount County.

The army passed the present site of Maryville, Tennessee, and on Friday, October 18th, crossed the Little Tennessee River near Toqua, probably at Tomotley Ford. That night was spent at Tomotley, the site of a Cherokee village downriver from Toqua. No opposition was found and next day the forces of Col. Christian marched downriver, on the south side of the Little Tennessee passing through Tuskegee, then past the site of old Fort Loudoun, which was destroyed by the Cherokees in 1760, to the Big Island Town (Mialaquo). Col. Christian made his headquarters at Big Island Town near the present Vonore, Monroe County, Tennessee.

The army camped near the Indian towns about six weeks and probably returned to their homes sometime in December. Rutherford’s campaign covered present day counties of McDowell, Buncombe, Haywood, Jackson, Macon, Clay, and Cherokee. Christian’s campaign covered present day counties of Sullivan, Washington, Greene, Cocke, Sevier, Blount, and Monroe (TN).

Jennifer Baker, DAR Vesuvius Furnace

Jennifer Baker, DAR Vesuvius Furnace