- Wednesday, 11 March 2026

- Have a HOT TIP? Call 704-276-6587 or E-mail us At LH@LincolnHerald.com

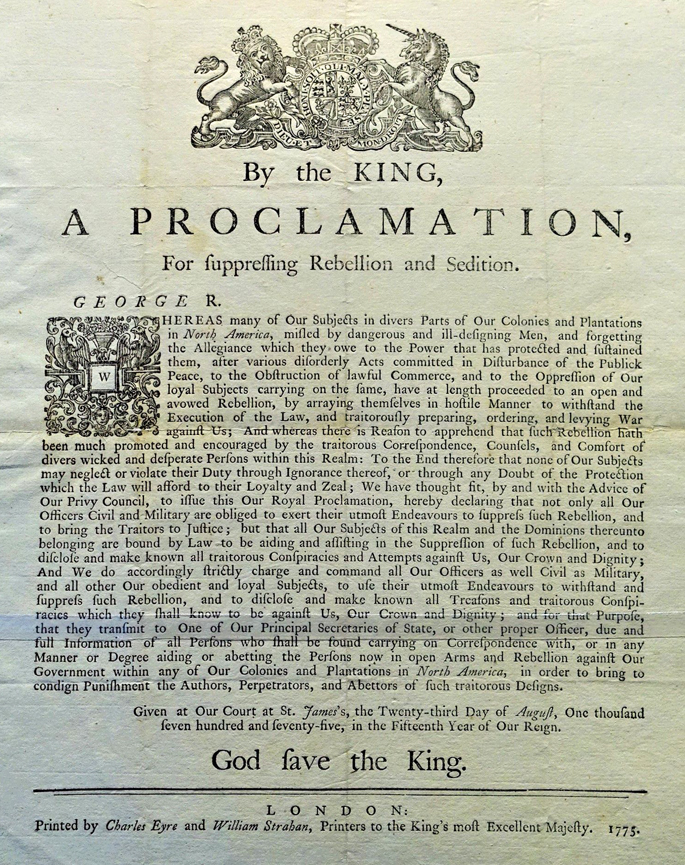

Proclamation Of Rebellion

Articles from the SAR and DAR leading up to America's 250th birthday in 2026

(Photos Courtesy Wikipedia)

In this, another in the series of articles from the SAR and DAR leading up to America's 250th birthday in 2026, we learn more about King George III and his Proclamation of Rebellion.

On August 22, 1775, King George III proclaims the American colonies to be in open rebellion and orders his officials to suppress it. Officially titled A Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition, was the response of King George III to the news of the Battle of Bunker Hill at the outset of the American Revolution. Issued on 23 August 1775, it declared elements of the American colonies in a state of "open and avowed rebellion". It ordered officials of the empire "to use their utmost endeavours to withstand and suppress such rebellion". The 1775 proclamation of rebellion also encouraged subjects throughout the empire, including those in Britain, to report anyone carrying on "traitorous correspondence" with the rebels to be punished.

The Proclamation of Rebellion was drafted before Colonial Secretary Lord Dartmouth had been given a copy of the Second Continental Congress's Olive Branch Petition. Because King George III refused to receive the colonial petition, the Proclamation of Rebellion of 23 August 1775 effectively served as an answer to it. Lord Frederick North was the Prime Minister of England from January 1770 until March of 1782.

On the 27th of October in 1775, Lord North's Cabinet expanded on the proclamation in the Speech from the Throne read by King George III at the opening of Parliament. The King's speech insisted that rebellion was being fomented by a "desperate conspiracy" of leaders whose claims of allegiance to the King were insincere; what the rebels really wanted, he said, was to create an "independent empire". The speech indicated that King George intended to deal with the crisis with armed force and was even considering "friendly offers of foreign assistance" to suppress the rebellion without pitting Briton against Briton. A pro-American minority of members within Parliament at the time warned the government was driving the colonists towards independence, something many colonial leaders insisted they did not desire.

On the 6th of December in 1775, the Continental Congress issued a response to the Proclamation of Rebellion saying that, while they had always been loyal to the King, Parliament never had legitimate claim to authority over them, because the colonies were not democratically represented. Congress argued it was their duty to continue resisting Parliament's violations of the British Constitution, and that—while they continued to hope to avoid the "calamities" of a "civil war"—would retaliate if any supporters in Great Britain were punished for "favouring, aiding, or abetting the cause of American liberty."

The King's proclamation and the speech from the throne undermined moderates in Congress like John Dickinson, who had been arguing the King would find a way to resolve the dispute between colonies and Parliament. When it was clear that King George III was not inclined to act as a conciliator, attachment to empire was weakened, and a movement towards independence became a reality, culminating in America's Declaration of Independence on 4 July 1776.

(Below - File Image: Proclamation of Rebellion, August 23, 1775 - Museum of the American Revolution by Joy of Museums.jpg)

Jennifer Baker, DAR Vesuvius Furnace

Jennifer Baker, DAR Vesuvius Furnace